Our Trip

Pictures tell a story that words often can’t—they capture emotion, connection, and moments that matter. Here are some images from our trip that reflect our journey of learning, reflection, and the power of education in action.

Pre-Work

In the weeks before our first class, we were tasked with reading several chapters of the book Freedom’s Children: Young Civil Rights Activists Tell Their Own Stories by Ellen Levine. Here are the chapters we read to help us set a baseline for our study of the Civil Rights Movement:

Chapter 1: The Color Bar: Experiences of Segregation

Chapter 2: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

Chapter 4: Sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and Other Protests

Chapter 7: Bloody Sunday and the Selma Movement

You can find a link to the book below if you would like to read it yourself.

We departed Monday morning, July 21st, from the Columbus airport and arrived in Atlanta, Georgia, around 10 am. After arrival, we met our tour guide, Mettina, and our bus driver, Ms. Mika. We toured several well-known areas of Atlanta, including a visit to the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site, where we explored the Visitor Center, Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, Freedom Hall, MLK’s birth home, and the Behold monument.

Site Experts: Student Speeches

The objective was for the students to become experts on key landmarks of the Civil Rights Movement visited during the trip. Before traveling, each student researched their assigned site to understand its historical significance, key figures involved, and the events that took place there. When we arrived, the students delivered 1–2 minute “elevator speeches” to the group—brief presentations that shared important facts, offered personal insight, and helped everyone connect more deeply with the site. The goal was to educate and inspire classmates by bringing history to life right where it happened.

On Tuesday, July 22nd, we traveled to Montgomery, Alabama. On the way, we visited the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site and the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University. Once in Montgomery, we explored the Alabama State Capitol, took a walking tour focused on the fight for voting rights, and toured the Museum of Alabama. We ended our day at the Civil Rights Memorial before heading to the hotel, where we gathered—just as we did each evening—to reflect on and discuss the day’s experiences.

-

I want you to imagine walking out onto an airfield in Alabama in 1941, the same field where the first groups of black men in U.S. History trained to become military pilots. Now, I would like to welcome you to Moton Field, where those said black men trained right here. Nestled on two hangars, this served as the training ground for over 1,000 black aviators who would later participate in the war effort during World War II, while also being supported by the famous First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt. These courageous young aviators, such as Benjamin O. Davis Jr or Chief Anderson, broke through segregation and aided in World War 2 by defending the skies above Europe. And eventually, their success helped shatter stereotypes and helped begin the desegregation of the military, paving the way for Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order, Order 9981, signed in 1948, which abolished racial segregation in the U.S. Forces, becoming a pivotal step in the broader Civil Rights Movement. Today, this National Historic Site honors their memory with historical exhibits, ensuring that we never forget their stories. And as we wrestle with equity even today, the Tuskegee Airmen demonstrate that even the most significant accomplishments begin when ordinary people are given a chance.

-

This museum tells the story of African Americans in the South, especially in Alabama. It shows the hard and painful parts of history, like slavery and racism. But it also makes you think about powerful stories of strength, education, and change. The museum is located on the campus of Tuskegee University, which Booker T. Washington started. Fun fact: he’s the same person Booker T. Washington High School was named after, which is where Claudette Colvin went!!

Booker T. Washington believed that education could help Black Americans build a better future. The museum is best known for teaching about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Henrietta Lacks story. These stories show how African Americans were treated unfairly in medical research and highlight the importance of ethics in science.

This museum carries a lot of emotional weight. It helps us understand the struggles of the past and honors the strength of the people who fought for equality.

-

The Alabama State Capitol is first and foremost the state capitol. But it is also an incredibly important landmark in the civil rights movement. In fact, it is arguably more important as a landmark than as a state capitol. Across the street is MLK Jr.’s church, the Dexter Avenue Church. Also of note is the memorial on the state capitol’s grounds. If you take a quick, wayward glance, you may note that it is of Jefferson Davis, who was the president of the Confederate States of America. I cannot stress enough how vile it is to leave such a memorial up, let alone right across from such an important part of The Civil Rights movement. Alabama’s history with the Confederacy is horrid, and it makes since why it is home to the most racist city in America. As of 2019, Jefferson Davis’s birthday is still a holiday that gives time off from work and school. The Capitol also featured several Confederate state battle flags, which the governor ordered taken down in 2015. That means we are hitting a decade of the Capitol having one less Confederate flag. Now, I wish they would take down that insipid memorial next.

-

(coming soon!)

On Wednesday, July 23rd, we returned to the Legacy Museum, where we spent a significant amount of time taking in its powerful, immersive exhibits on the history of slavery, mass incarceration, and racial injustice in America. The museum prompted deep reflection and conversation, setting a meaningful tone for the rest of the day. From there, we visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a striking outdoor memorial honoring victims of racial terror lynchings. In the afternoon, we explored the Freedom Rides Museum, located in the historic Greyhound bus station, where we learned about the bravery and resilience of the young activists who risked their lives challenging segregation in interstate travel. We concluded the day at the Rosa Parks Museum, where we gained deeper insight into her courageous act of resistance and the broader Montgomery Bus Boycott. Each site added layers to our understanding of the Civil Rights Movement and the ongoing struggle for justice.

-

It was once said by Frederick Douglass that “Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.” And safe from those who degrade justice, we are not.

This museum is more than just the history of the practice of enslaving Africans in America, this museum is the showing of continued oppression of African-Americans, and how oppressors reach further into the past to make the present more miserable. Despite opening in 2018, the history of the lessons this museum teaches goes far beyond the present time, being close by to one of the largest slave auction sites in the state, and a railroad that carried tens of thousands of slaves by the day in the 1800s. And even afterwards, showcases the present-day mass incarceration of African-Americans, and the disproportionate amount of Black men in prisons during the Civil Rights Movement, and today.

Learning about the injustices of African-Americans throughout history means actions can be taken by all colors and people to secure a future without privilege of skin and not to create harmful guilts and woes, but to secure a future where understanding, acknowledgement, and action are taken to bridge the divide between people in this nation together. These teachings reflect and showcase the horrors of slavery, racial terrorism, racial supremacy, and shows the unsanitized history and uncomfortable truths that we must come to recognize.

Through painful imagery brought to life in statues, aims of reconciliation, and learning of the wrongs of the past, may this be the teachings for all to reconcile with these injustices, for a truly equitable society.

-

According to the NAACP, “4,743 lynchings occurred in the U.S.” from 1882 to 1968, though it’s hard to tell because they weren’t ever formally recorded. Lynchings weren’t just about killings; they also “marginalized [b]lack people politically, financially, and socially.” In a world where we’ve become so desensitized to statistics, I’d like to ask you all to consider how much 4,743 really is. Imagine every single face, every single life, taken by false or minor accusations, if any at all.

On April 26, 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice became America’s “first memorial” meant to honor victims of lynching and white supremacy in general. In six acres, the memorial utilizes sculpture, art, and design to “contextualize” racial terror. In the center, you’ll see a structure made of 800 steel monuments, each one representing a county where a lynching took place. The Equal Justice Initiative, or EJI, collaborated with artists like Kwame Akoto-Bamfo and Dana King to force viewers to confront racial injustice from beginning to end. We start from slavery, going to lynching, the fight for civil rights, and ending with modern police brutality.

It mattered then because no one was there to properly honor lynching victims as a collective, to properly honor deaths from unnatural causes like white hatred. It matters now because black people still haven’t received proper reparations for their mistreatment. While it seems so long ago, lynching only ended in 1968. And it was only officially recognized as a hate crime in the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, introduced in 2022. That’s only 3 years ago, where lynching gets you “no… more than 30 years” in prison.

Remember how we discussed how long it took for justice to be served in class, how long it took for the government to take action only under extreme tragedies. The very least thing we can do is acknowledge our country’s sins and remember the martyrs who died during this turbulent time. Thank you.

-

Despite the desegregation of buses, interstate bus systems, one of which being Greyhound, were still segregated. Because of this, a group of white and black activists decided to protest by riding these buses together in 1961. These were the freedom riders. The first bus left Washington D.C on May 4 and the plan was to arrive in New Orleans on May 17, riding through the south which was still deeply rooted with hatred. The first few days went by uneventfully for the riders until they arrived in Alabama, a severely racist state. There were two buses, one on route to Birmingham and the other on its way to Anniston. The Anniston bus was met with a mob of about 200 white people and when they tried to escape, a bomb was thrown into the bus with the intent to kill the riders. Miraculously, all the riders survived despite the white mob holding the doors of the bus closed after the bomb had gone off. The Birmingham police gave the KKK the go ahead to attack the freedom riders and later used the fact that it was Mother’s day as an excuse as to why the violence was able to occur due to a “lack of officers”. The KKK, a hateful group that covers their face and believes in white supremacy and attacks average civilians for how they look. Some might say this bears resemblance to a certain government funded agency that is (in a way) attacking average citizens based on their appearance. It’s a hard pill to swallow, knowing that the same government that swore to protect you, is doing exactly the opposite and allowing hateful groups to commit terrible acts of violence to anyone they deem a “threat”, especially if it's a group of peaceful protesters because we all know how dangerous people holding signs can be to those armed with hunting rifles.

-

“You must never be fearful about what you are doing when it is right.” Rosa Parks spoke these words more than half a century ago, after being arrested for not giving up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. It was only after six others had tried this, that the seventh, Rosa Parks, had successfully sparked the largest, and longest American boycott in recent history. Where we are right now, is where Rosa Parks made history on that bus.

She was a 42-year-old African-American seamstress and NAACP member for over a decade who refused to give up her seat on a segregated city bus to a white rider. After her arrest, she sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a twelve and a half month, or 381 day protest organized by local Black leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., E.D. Nixon, and the Montgomery Improvement Association. The boycott, which began a few days after Parks' arrest, was a giant act of civil disobedience on the part of the Black community, refusing to ride the bus until the city relinquished its policy of racial segregation. Coordinated in carpools, and walking groups. The boycott became one of the largest mass actions of the Civil Rights Movement. So Rosa Parks showed that faith in her community, and an act as small as a mustard seed can create an unstoppable unity between people

The museum matters because it is not just a museum, but a celebration of resilience, and the simple “no” that led to the Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle (1956), which made segregation on public buses unconstitutional. The site includes a walk through of a restored 1955 city bus, and even one of the station wagons used for carpooling during the boycott. It also shows how important strategy, teamwork, and especially women were to making the movement successful. In the Children’s Wing, there’s an exhibit called the Cleveland Avenue Time Machine that teaches younger visitors about the roots of racism through a recreation of the Jim Crow Era with the goal of educating through visuals.

So it is a place for all people to experience what it meant when Rosa Parks said no. And how powerful it was to the civil rights movement.

On Thursday, July 24th, we traveled to Selma, Alabama, where we explored the town and visited the Old Depot Museum to learn more about local history and the fight for civil rights in the region. One of the most powerful moments of the day came when we walked across the historic Edmund Pettus Bridge, reflecting on the courage of those who marched there during Bloody Sunday in 1965. We then toured the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute, a grassroots museum led by a small group of dedicated individuals who generously shared their stories and knowledge with us. In the afternoon, we departed for Birmingham, where we would spend the night. On the way, we visited Kelly Ingram Park—a site of intense civil rights demonstrations—and the 16th Street Baptist Church, where we honored the lives lost in the 1963 bombing and considered the church’s enduring legacy in the movement for justice and equality.

-

We are currently standing in front of/on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. When I see this bridge the first question I have is: who is Edmund Pettus? This key point on the march from Selma to Montgomery was named after a decorated Confederate general. He was born in 1821 to wealthy planters who greatly benefited from owning slaves. He was part of a group that lobbied the governor of Alabama, his brother John Pettus, to secede from the union. After the Civil War, he returned to Selma, a war hero to the southern whites. He was the leader of the KKK in Alabama who later used his white supremacist rhetoric to win seats in the senate until his death.

The bridge opened thirty-three years after Pettus’ death, and in 1940 it was a key part of the cotton trade. John Giggie, history professor at the University of Alabama, wrote in the Smithsonian, “the bridge was named … to memorialise his history of restraining and imprisoning African-Americans in their quest for freedom.’”

This is the place where Bloody Sunday and the Selma to Montgomery March took place, and it conflicts that a place that is so important when you think of the Civil Rights Movement of the sixties with this man who stands for everything the Movement was fighting against. There have been two unsuccessful attempts to change the name of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. In 2015 Selma based activists made a petition in February that gained 150,000 signatures by March. 2015 was the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday and many people came to Selma to commemorate it including President Obama, but unfortunately the KKK used the influx of people to try to recruit members. The petition was never voted on in the house. The next attempt to rename sparked after the death of C.T. Vivian and John Lewis on the July 17th, 2020. A petition to name the bridge after John Lewis got 500,000 and a stretch of highway including the bridge was almost named after him, but the amendment got stuck in legal purgatory.

I still can’t get over the fact this bridge is still named after this horrible man who is idolized by neo-confederates today. It feels like a complete slap in the face that this horrible, terrible man is going to be eternalized in history for forever.

-

From each Presidential election from 2012 to 2024, an average of over 88,000,000 registered voters did not vote in each of those elections. Meaning that their voice could have meant something in this democracy, but chose to stay silent and at home. The National Voting Rights Museum and Institute is dedicated to upkeep and to visually narrate the history of the struggle for fair voting rights for African-Americans in the United States. After President Lyndon Johnson signed the voting rights act on August 6th, 1965, nearly 7,000 African Americans registered to vote in Dallas County, Alabama. The fight for African American voting rights was a grueling battle for justice, and in a world where white supremacy was led, and Black people were skinned bare of their humanity, Black people united together in their shared belief of the promise of the constitution, and having each step they took and hymn they sung ring through the city to let all know that they are here and will be heard. The museum looks back on the sacrifice and courage of those who fought for their and future generations' right to vote, and to have black political power to rise within officials to create a true democracy. Voting Rights injustices are still going on today due to ongoing voting suppression by not having votes of certain communities count against their knowledge, meaning that the struggle for equal access over the ballot is not over. Moving forward, we must learn from the past, enable to create change, we have to speak out, to make our voices known and show that united voices cannot be ignored.

-

Everyone look at the streets surrounding this park. These streets are where firemen used their firehoses to attack peaceful protesters, many of which were children. Firehoses that were turned to the highest setting available. The same firehoses that could peel bark off of a tree. In the 1950s, Birmingham was known as America’s most segregated city. Black residents were only given 11% of the residential zoned space in the city even though they made up nearly half of the population. Jim Crow laws separated black people in buses, pools, elevators, lunch counters, drinking fountains, and even this park we're standing in.

Kelly Ingram Park was built in 1871, at the time called West Park. The park was renamed in 1932 after local firefighter Osmond Kelley Ingram who was the first sailor in the US Navy to be killed in WWI.

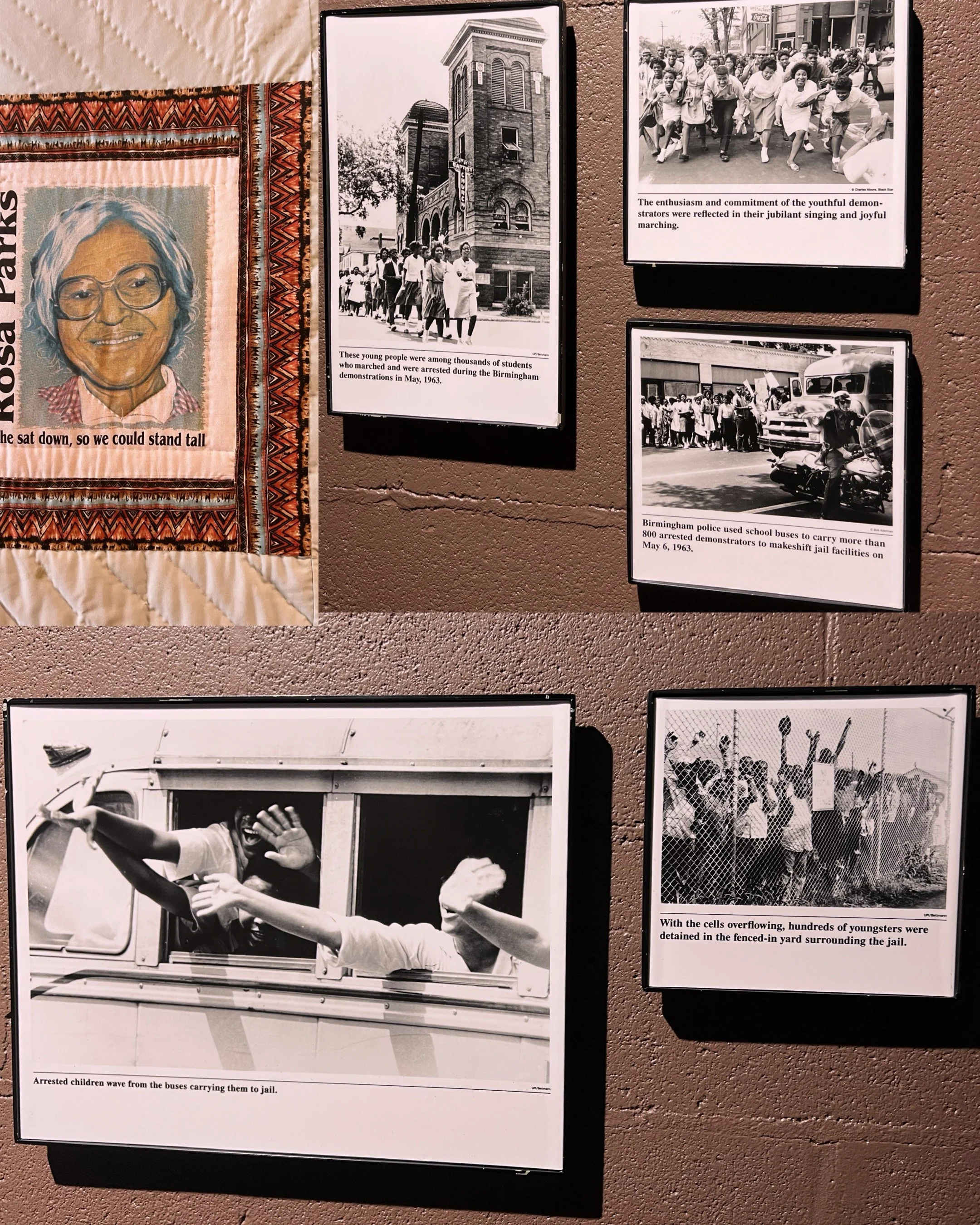

After the violent attacks on one of the early Freedom Ride buses, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference decided to host a massive protest campaign in Birmingham. Kelly Ingram Park was a meeting place for the people who participated in sit-ins, protests, and jailings with the intent of ending segregation. So many people were arrested that the SCLC called for children to begin protesting. Little did they know, that wouldn't stop Commissioner Bull Connor from allowing what happened on these streets.

These statues we see around us depict the struggle for civil rights here in Birmingham. Kelly Ingram Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

On our final day, Friday, July 25th, we returned to the 16th Street Baptist Church for a guided tour that offered deeper insight into its history, the tragic 1963 bombing, and the church’s powerful role in the Civil Rights Movement. We then spent time at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where interactive exhibits and powerful stories helped us connect the past to the present. Next, we visited the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, which commemorates key sites in the city’s fight for racial justice. Before heading to the airport, we made a meaningful final stop at Bethel Baptist Church, the former home of Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and a hub of Birmingham’s civil rights activism. From there, we made our way home—carrying with us the stories, lessons, and reflections from an unforgettable week.

-

Addie Mae Collins. Denise McNair. Carole Robertson. Cynthia Wesley. On September 15, 1963, these four girls, ages 11 and 14, were killed by the Ku Klux Klan’s bombing of the 16th street baptist church. This was an extremely targeted attack; the church a home to organizers from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to Martin Luther King Jr in the “most segregated city in the United States.” This was fueled by Alabama’s Governor George Wallace’s call for “a few first-class funerals” to solve the States’ race problem. Before September 15th, 21 other bombings of Black homes and churches had pillaged the city. This time was different; people were killed. After the bombing, people sprang into action: organizing rallies and the Alabama Project for Voting Rights, which led to the march from Selma to Montgomery and eventually the V oting Rights Act. They fought back against Governor Wallace’s criminal promise of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” and the over 300 police officers set loose on protesters in Birmingham. The summer of ‘63 in Birmingham had already been a violent summer, but this event set it over the edge. People were angry and frustrated, their protests met with police violence and arrests: a headline still common today. Ten months later, after federal law enforcement intervention, national outrage, and countless protests, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act: direct response to the national cry for justice for the four girls murdered in their place of worship. This bombing ended the lives of four girls and changed the US forever, but at the cost of violence. Still today, federal action only seems achievable after the lives of innocent people are lost.

-

Upon this piece of land where the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute stands today, more than half a century ago in 1963, some of the most major Civil Rights protests took place. In words commemorating this struggle more broadly, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth said: “Some men may little note or soon forget what we say here: but the Nation will never forget what we did here together. We were not satisfied with the few scattering cracks in the Segregation wall, and decided to effect a major confrontation with evil.”

And so, in 1978, Birmingham mayor David Vann idealized a place where the struggle for freedom could be memorialized. Unfortunately, he was not able to fulfill his mission, but his successor, the first black mayor of Birmingham, Richard Arrington Jr., was. The Institute is the culmination of a dream; the dream of a city hoping to confront its past of prejudices, and a large, multi-racial cohort of its constituents, to preserve the core lessons and victories of the Civil Rights Movement in an educational center where they could be a positive influence on future generations. By their fervent efforts, the city of Birmingham finally opened this institute in 1992. The founding President, Odessa Woolfolk, says “The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute signifies that Birmingham does not hide from its past…Birmingham now embraces its past, neither forgetting nor dwelling on it, but using it to foster understanding.”

This building isn’t just a collection of exhibits that illustrate the movement, but the symbolic titan of hope which powered it. In another world, perhaps this building would not be here. Maybe it would be the sight of protests that eventually fizzled out at the hands of brutalistic police, and a statue of a proud George Wallace would be erected in its place. But there’s a reason that didn’t happen here, and that is due to the unrelenting and passionate desire for freedom, and the spirit of hope which reigned among the brave men and women of the movement. In the present day, their faces and words and battles for liberty are encapsulated among these walls.

-

It was a quiet night on Christmas in 1956, Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth and his family were fast asleep in Bethel Baptist Church which they also called home. But all of a sudden a loud BOOM destroyed the church, and with Rev. Shuttlesworth and his family inside no one would have expected them to survive, but not only did they survive, they walked out of the rubble almost unharmed. This was just one of the 3 times that white supremacists had tried to bomb the church to destroy it.

Bethel Baptist Church was constructed in 1926 in the neighborhood of Collegeville, Birmingham and was a safe space for the black people in the community to go every Sunday. But as soon as the civil rights movement started the church became the center of attention for just about everyone in the movement. It was the place where meetings took place for the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) and was where tons of demonstrators planned and organized nonviolent protests to get equality in one of the most racist cities in the country. It was a key location for the Freedom Rides in 1961 and the church provided safety for those making the trip into Birmingham. It was a key location in the movement and those that used the space helped to get the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed despite the efforts to stop it from the racists in Alabama.

Now the original church is a historic site and visitors can go inside and sit in the same pews that churchgoers used to and watch a documentary on the life of Rev. Shuttlesworth. Without this church many of the rights that we have today may not have come or would have come at much later point. But in the end, it is very important to recognize the significance of this church and how important it was to ensuring that black people across the country got the rights and recognition they deserved.